|

1.5 FILES, RECORDS AND LOGBOOKS

Few things are more important to the continuity of a tanker's operations

and maintenance programs than a complete set of accurate records. On

a modern ship, payroll, overtime, maintenance, inventory and requisition

records are all maintained on a computer. If it is well designed, the

modern computer system leads even the most computer-illiterate officer

through a menu selection system which makes the necessary entries both

sailor-proof and quick. Modern software eliminates mathematical work

and errors - it is only necessary to make the entries correctly. Each

of the company's reports can be programmed for 'step through' entry,

followed by printing of a perfect copy or direct transmission by modem

to company headquarters. Any new computer version should use the forms

of the existing reporting system. It should be carefully tested by management

prior to implementation. After the initial version has been in use for

a time, crew recommendations should be sought and used for making improvements.

'Package' ship records systems are available. They avoid the costs of

custom programming, but any off-the-shelf program should be fully reviewed

by the crew before it is purchased for their use. Some of the programs

are easy to use, while others are so 'user-hostile' that the crew would

be better off with an old, bound-journal system. A well-designed shipboard

computer system will have password protection for the various files

and programs so that only authorised users (master, chief officer, chief

and first assistant engineers) can access or edit critical data.

Whether the ship's record keeping system is manual or computer based,

each officer must continue to conscientiously maintain it. This is particularly

true in the case of 'relief officers replacing a 'permanent' crew member.

When the regular officer returns, he will be delighted to find that

his records and files are up to date. If they are not, he is sure to

make some bitter comment to the master before or after the relieving

officer's departure!

Every document included in the ship's records must be dated (including

the year!), and include the legibly printed name and signature of the

person who made the entry or completed the report. Professionals are

proud of their work and like others to know who did it. They sign their

logs and reports in a way that leaves no doubt about who did the good

work that was recorded there.

Some of the more important records are:

Crew training.

Payroll and overtime.

Cargo orders.

Voyage records.

Cargo system tests.

Oil record book.

Deck and engineer logs.

Safety inspections, meetings and drills.

Preventive maintenance.

Classification society inspections.

Loading and discharge records.

Cargo tank cleaning.

Shipyard repairs.

Accident/incident reports.

Port state inspections.

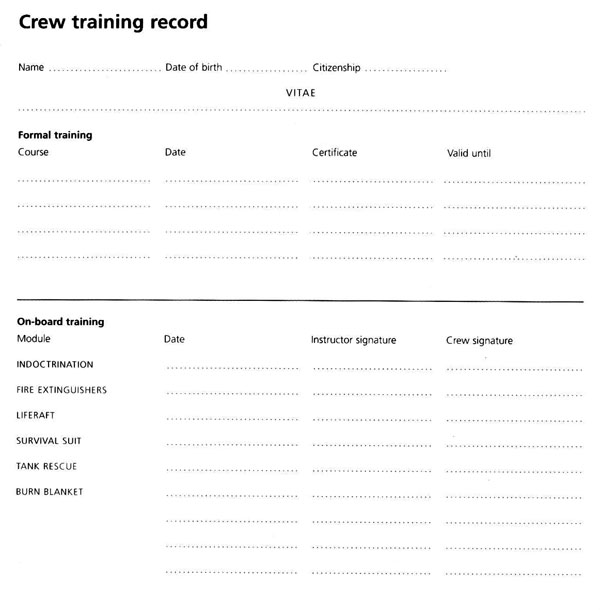

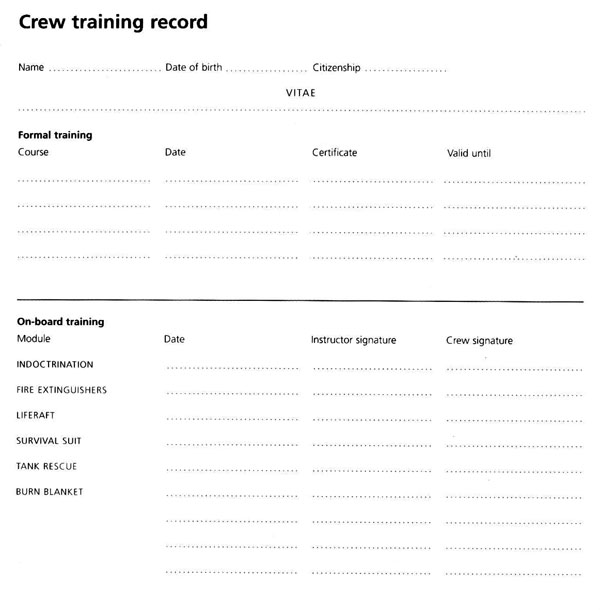

1.5.1 Crew training records

At a time when qualified and experienced crews are becoming more difficult

to assemble, maintaining an active training program is the only way

an owner can insure that his personnel know their jobs. Records are

essential to insure that each employee completes all required training

and that training progress is documented. These records can have additional

value in helping to defend the owner against injury and pollution claims.

They demonstrate that the seamen were given the training necessary to

recognise and avoid the hazards of their employment and that a conscientious

program of anti-pollution indoctrination was followed.

On the day they first report aboard a new ship, crew members should

be given a familiarisation tour of their workplace and emergency duty

stations. This will be entered on their record. The crew member should

initial or sign the entry for his indoctrination tour and for each training

session completed while on board. The report sheet should be sent to

the office when the crew member leaves and forwarded to the next ship

he rejoins. Vessel training records should be reviewed by the personnel

director to determine the kind of training needed on board. They should

be retained as proof of training conducted.

An individual crew training record. The crew member's

signature proves that training was received.

1.5.2 Preventive maintenance records

Conscientious owners appreciate the value of programmed maintenance.

Over the long run, it preserves both earnings and the resale value of

their ship. Such programs are entirely dependant on accurate record

keeping. Each cycle of a system's maintenance should be completed on

time and all completed work must be recorded. When the completed work

has been entered in the computer program, the computer will be able

to determine when the task is due to be repeated. Vessels which are

on a classification society continuous machinery inspection program

depend on accurate and complete records to maintain inspection exemptions,

else costly 'open and inspect' requirements may be imposed.

If an officer joins a ship which does not have a maintenance logbook

for his collateral duties, he should start one. Even if he is a third

officer in charge of only the bridge navigation equipment, flags, and

lifeboat inspections, he should have a small journal to record inventories,

inspections completed and repairs/exchanges made. With even a basic

record system, the job will be done better and it is good practice for

other duties as the officer advances in rank.

With a complete lifeboat inspection record in his journal, a young third

officer will not need to freeze in the lifeboats if the chief officer

asks for an inventory of the expiry dates of all the lifeboat stores

when the ship is a day from arrival in Montreal in December!

Two of the chief officer's important maintenance records are the maintenance

logbook and the individual equipment records. The chief officer records

all work completed by the Deck department in his maintenance logbook

each day. At a later date (see section 4.6),

this log is reviewed and the specific equipment journals (hand written

or computer) are brought up to date. If the individual equipment records

are kept as file folders, the files should be arranged according to

the company file code system, or genetically (military style). If the

ballast pump is a 'Watrous' design do not file its records under 'W'.

File them under 'Pump, Ballast, Maintenance'. Clearly label each file

and use a suspension-type file system.

1.5.3 Safety records

The position of ship's safety officer should be rotated among the deck

and engine officers. Each in turn is required to complete and record

the necessary routine inspections and to audit the other department

for proper safety practices. Records of all safety meetings, inspections

and safety equipment are maintained. The safety officer should schedule

(or follow the company schedule for), the emergency drills and safety

training program.

The safety records demonstrate that the latest safety advice, casualty

reports and instructions have been properly disseminated to the crew,

who are the end users of this important information.

1.5.4 Overtime records

Overtime records are essential to support charterer's invoices, proper

payroll administration and for reference in preparing future budgets.

In the event of a casualty, investigating authorities may examine these

records to evaluate the contribution of crew fatigue to the accident.

1.5.5 Cargo records

Few areas of a tanker's operations result in more claims than the handling

of the cargo. A tanker cannot hope to prove 'proper care' of a petroleum

cargo unless full and complete records are available for presentation.

Cargo records which may become important to a cargo claim inquiry include:

Loading

Charterer's loading orders.

Tank washing, cleaning and preparation programs; slops recovered.

Ballast plan.

Tank inspection certificates.

Chief officer's loading instructions.

Declaration of inspection prior to cargo transfer.

Ship's ullage sheets and loading quantity calculation.

Shore tank ullage sheets and quantity calculation.

Cargo analysis report/quality certificates.

Ship's deck and engine, rough and smooth logs and port log.

Cargo manifest/bill of lading copy.

Cargo heating instructions and heating records.

Oil record book.

Slop/sediment declared at loading port.

Slop disposal certificate.

Fuel loaded documents.

Arrival and departure reports.

Dead-freight or short lifting calculations.

Notes of protest

Discharging

Ship's arrival ullage report.

Charterer's discharge instructions.

Chief officer's discharging instructions and logs.

Cargo pump operations record/log.

Ship's port log sheet.

Ship's tank inspection certificate.

Shore tank ullage sheet and quantity calculation.

Cargo exception reports.

Chief officer's ballasting instructions.

Notes of protest.

Check lists used for the efficient performance of cargo operations should

be retained as an important part of the cargo and voyage files.

Cargo forms for the previous six cargoes must be readily available. Two

copies of each form and report should be maintained. One copy is part

of a consolidated cargo file for that cargo, filed as a group by voyage

number.

The second copies are kept in files or ring binders by report type. This

makes it easy for the chief officer to refer to past records when preparing

orders without disturbing the consolidated cargo file packages. Cargo

records must be sufficiently detailed to be useful to a claims investigator.

Port logs must show the sequence in which each cargo tank was loaded/discharged,

including the times of commence and finish loading/discharging each tank/product.

Also indicate into which cargo tank(s) the contents of the cargo lines

were dropped at the start and finish of loading or discharging and whether

such dropping occurred prior to or after gauging ROB.

Other records which may be requested include:

Summary of ports of call, including dates.

Letters of discrepancy for all voyages undertaken.

Superintendent reports.

Engine sea trial book.

Heating balance diagram.

Date last drydock, hull cleaning, leadline, US coast guard inspections.

Maker and type of anti-fouling paint in use.

Crew lists (all voyages) including home addresses and telephone numbers.

Leaks in cargo tanks or piping systems, dates detected, causes, repairs

made, repair test records and class inspection dates.

1.5.6 Inspection records

Most inspection records become part of the preventive maintenance or

safety record files. Those which do not should be filed separately according

to the equipment or system inspected, or with the classification records

as appropriate.

1.5.7 Cargo tank records

Records of cargo tank crude oil washing, cleaning, maintenance, repair

and modifications are important to proper cargo operations. These records

should be filed by tank, so that the history of any tank can be determined

from a single file.

1.5.8 Cargo system records

Pressure tests of cargo piping and leak tests on valves, replacement/

repair of pipe sections, valves or pumps, records of ultrasonic thickness

surveys and placement of temporary repairs should be included in these

document files. Temporary repairs must be permanently corrected at the

very first opportunity. Failure to do so will expose the vessel to charges

of 'unseaworthiness with respect to cargo' if a cargo contamination

should occur.

1.5.9 Shipyard records

Shipyard records are important for review in the event a repair fails,

or when preparing for the next repair period. They are also necessary

sources of information for correcting the ship's stability booklet.

A separate summary of significant weights added to or removed from the

ship, along with the location should be maintained. This can be compiled

from the shipyard record after repairs are complete.

1.5.10 Oil record book

One of the more important record books is the tanker's Official oil

record book. These records are required by Regulation 20 of MARPOL 73/78

and must be maintained in a form (and usually in a book) supplied by

the flag state authority. On 4 April 1993, the oil record book form

required by Appendix III of MARPOL 73/78 (1991 Consolidated edition),

became effective.

Entries are made by the chief officer according to the instructions.

Each page is signed by the master (see section 2.13.2).

1.5.11 Orders

The written orders prepared by the master, chief officer and chief engineer

must be retained on board as part of the ship's permanent records.

1.5.12 Accident/incident reports

The company may have a special accident/incident report form. If not,

it is important that notices of accidents or incidents contain at least

the following information:

Name of the vessel.

Time and date of the incident.

Personnel involved, their crew position, years of service.

Person in charge of the operation.

Location of the incident on board.

Weather and other influencing factors (noise, lighting, footing, etc.)

Personnel injuries.

Damages which occurred, or which might have occurred due to near miss.

Estimated cost of damage and loss.

Possibility of reoccurrence if nothing is done.

Recommended actions to prevent reoccurrence.

Loading port and date of loading.

Discharge port and date.

Quantity and type of cargo.

Nature and extent of damage.

Total number and reference numbers of Bills of Lading.

1.5.13 Records retention

Each vessel owner should have a records retention and disposition program

for his ships. This program will indicate which records must be maintained

in file form, how long they are to be retained on board the ship and

how they should be disposed of (transferred to the Home Office or destroyed),

at the end of that time.

1.5.14 Logbooks

The logbook is the official record of the ship. In it should be recorded

a detailed record of the activities of the ship and her crew. Each significant

point during a voyage and each operational change while in port should

be clearly entered. Logbook entries should be concisely detailed, that

is, all important information should be recorded by brief notations.

As an example, the entry '14.38 - began loading cargo' is concise, but

lacks essential details. In a later, investigation of this cargo operation,

this logbook entry would provide no information regarding the way in

which cargo was loaded, or what happened to the No.2 oil later found

to be off-test. The entry '14.38 -began loading No.2 oil into tanks

Nos. 3 across, 4 wings and 5 centre, via No.2 line and deck drop' provides

all essential information to determine how the No.2 oil was loaded into

the ship. Each step of the cargo operation should be recorded, from

all fast on arrival through last line aboard on departure.

Logbook entries must be clearly printed, in neat, hand printing. The

watch officer should sign the last entry of his watch with a legible

signature. The style of logbook entries may vary from ship to ship.

For the new officer, a cursory examination of the previous voyage and

port entries will indicate what the accepted practice is on the ship.

All logbook entries must be true and correct to the best of the understanding

of the officer making the entry. If there has been an unusual event

on the watch, the officer may first draft his logbook entry in rough

and review it with the master before making the entry in the logbook.

No erasures arc permitted. An error should be ruled through with a single

line, initialled and then then correct entry made immediately after.

The master may make navigation entries, or entries regarding the crew

as necessary, or may instruct the watch officer to do so. The chief

officer may make entries regarding cargo operations, or instruct the

officer to do so. If there is any controversy regarding a logbook entry,

the entry should be made and signed by the officer who wishes the entry

to be made.

|